Why do regulators in developing countries, particularly low- and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), respond differently to international banking standards? Our research starts with the recognition that the scope and depth of Basel II and III adoption in LMICs is not merely determined by technocratic assessments of suitability and fit. Instead, regulators’ decisions are influenced by the political economy of relations among key domestic actors, and the wider domestic and international context they operate in. The three key domestic actors are: the regulator (usually situated within the central bank), large banks, and incumbent politicians.

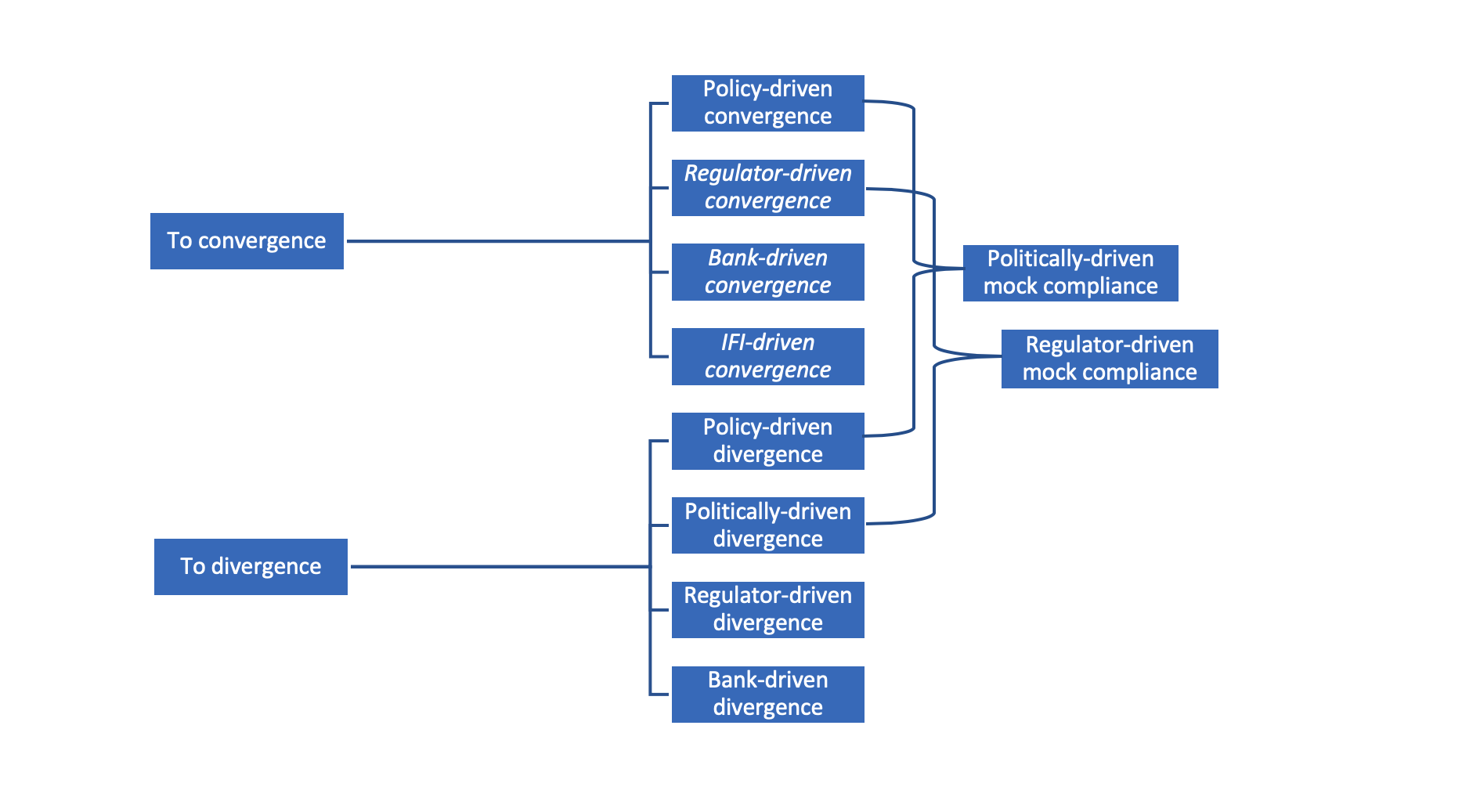

To explain variation in the responses of regulators to international banking standards, we identify four factors that drive convergence, and four opposing factors that incentivise divergence.

Convergence

- Politicians seeking international capital: Politicians may wish to adopt international standards as it is perceived to be an important signal to investors that their banking system is soundly regulated, thus attracting more capital.

- Regulators engaging with peers: Through interactions with peers in countries that are implementing the standards, regulators in peripheral developing countries may end up following suit.

- Domestic banks expanding into international markets: International banking standards may be adopted to facilitate the expansion of internationally oriented domestic banks into new markets.

- Engagement with international finance institutions (IFIs): IFIs have taken diverse approaches to the adoption of Basel standards, promoting implementation of some but not all of them. In general, we expect regular and extensive engagement with the IFIs to result in higher levels of implementation, however this may fall short of support for implementing the full suite of standards.

Divergence

- Politicians pursuing interventionist financial policies: Where governments wish to direct credit to specific sections of the economy or particular societal groups, this is likely to create incentives to diverge from the implementation of Basel standards.

- Politicians and business oligarchs using banks to direct credit to allies: In order for such political allocation of credit to be possible, politicians and business oligarchs wish to keep lending regulations lax.

- Sceptical regulators: Given the debate on the appropriateness of Basel standards for LMICs, particularly Basel II and III, it is very plausible that the regulatory authority will resist the introduction of international standards, particularly their more complex elements

- Fragile domestic banks: Banks with business models focused exclusively on the domestic market in peripheral developing countries are likely to oppose the implementation of complex regulations because of the additional compliance costs this generates.

Pathways

Due to the differing political, economic and institutional contexts, regulators experience incentives to converge and diverge through different channels and with varying levels of intensity. We distinguish between different pathways of convergence and divergence according to the reason or actor that predominantly drives the outcome. We also explain what might lead to 'mock compliance' ie formal compliance which is not put into practice.

To convergence

Policy-driven convergence:

- Led by incumbent politicians with a strong vision of integrating their countries into global finance and expanding the financial services sector, perhaps with the support of local business elites.

- Politicians may face resistance from the regulator, particularly if the regulator has limited expertise and resources, and from small domestic banks, particularly if they are used to a lax regulatory environment.

Regulator-driven convergence:

- Led by regulators, and is particularly likely when the regulatory authority has a high level of independence, and when senior officials engage extensively in international policy discussions and aspire to senior positions in international financial institutions organisations.

- Regulatory authority is likely to adopt a normative identity focused on the championing of ‘international best practices’.

Bank-driven convergence:

- Occurs when large domestic banks champion the implementation of international standards as part of a drive to expand into new international markets.

- These proposals are likely to be met with opposition from smaller banks, and inertia or opposition from the regulator and politicians. The outcome will depend on the political influence of the larger banks.

IFI-driven convergence:

- Occurs when implementation is championed by the IMF or World Bank.

- Where these are opposed by regulators, politicians and banks, little meaningful implementation is likely to occur (unless it is a condition for accessing financial support, which may lead to implementation on paper, but not in practice).

- If the regulatory authorities are supportive of implementation, then an alliance between IFIs and senior technocrats may be sufficiently powerful to convince politicians to push reforms through.

To divergence

Policy-driven divergence:

- Occurs when the pursuit of interventionist financial sector policies creates a mismatch between the need for the regulator to ensure that government and state-owned banks make informed, impartial, policy-based decisions in the direct allocation of credit, and the role envisaged for the regulator under the Basel framework.

Politically-driven divergence:

- When political and business elites have a vested interest in maintaining an opaque and highly personalised system of credit allocation.

Regulator-driven divergence:

- Occurs when the regulator seeks to block the implementation of international standards out of concern that they are ill-suited to the domestic context.

Bank-driven divergence:

- Likely to occur when a critical mass of domestic banks are weak and poorly governed, and implementation of international standards is likely to publicly expose their fragility. We expect regulators and politicians to support the weak banks, fearing reputational, economic and political fallout if they proceed with implementation.

To mock compliance

Politically-driven mock compliance:

- Occurs when politicians want to implement international standards in order to signal creditworthiness to international investors yet are concerned that implementation will limit their ability to direct credit for policy or political reasons.

Regulator-driven mock compliance:

- Occurs when the regulator wants to implement international standards in order to support the international expansion of domestic banks and enhance their professional standing in the eyes of their peers, yet is concerned that implementation will expose hitherto undisclosed weaknesses in capital provisioning by domestically oriented banks.