What are Basel standards and why do they matter?

The global financial crisis of 2008–9 showed the devastating impact that bank failures have for firms, workers and taxpayers, and the need for sound regulation and supervision of banks. Since the 1970s, central bank governors from the world’s largest financial centres – meeting under the auspices of the Basel Committee on Banking Standards - have come together to agree minimum regulatory and supervisory standards. Although intended for the regulation of large, internationally active global banks like JP Morgan and Citibank, the various iterations of Basel standards have become the reference point for regulators across the world.

The Basel Core Principles (BCP) have become the de facto minimum standard for the sound prudential regulation and supervision of banks systems around the world. Developed in 1997 and revised several times since, the Basel Core Principles apply to banks and financial supervisors. They set out minimum standards in a range of areas including regulatory independence, risk management procedures, and capital buffers. There is surprisingly little empirical evidence that compliance with the Core Principles actually improves the financial stability or the wider performance of the banking system. Nevertheless, countries are routinely assessed by the World Bank and IMF regarding their compliance with the Basel Core Principles.

Basel I was the first standard agreed by members of the Basel Committee. Published in 1988, it set minimum capital requirements for internationally active commercial banks commensurate to the credit risk they face. Critics of Basel I argued that it did not sufficiently differentiate the risk associated with individual loans, and it did not cover all types of assets.

In response to these concerns, the Basel Committee developed Basel II. Finalised in 2004, the revised standard features differentiated requirements for a wider range of financial risks. Moreover, it allows banks to use internal risk models to calculate capital buffers. Basel II has been widely criticised for dramatically increasing the complexity of the capital framework, and for being woefully inadequate in ensuring bank resilience, as evidenced in the global financial crisis of 2008.

Basel III seeks to address these concerns by raising the bar of prudential banking standards. Developed in 2012–17, it combines tougher capital requirements with new rules to cover a wider range of financial risks, including liquidity and systemic risks. Basel III is also the first standard to be negotiated with developing country representatives from the G20 at the table, although their degree of influence is unclear.

While many financial regulators around the world recognise the relevance of the Basel Core Principles and Basel I, the benefits and costs of Basel II and III adoption among LMICs are disputed. An immediate challenge arises from the sheer complexity of Basel II and III, since supervisory capacity is often an acute constraint. Weaknesses in financial sector infrastructure, particularly gaps in the availability of credit ratings and credit information, can also frustrate efforts to implement the standards. For more information on the challenges Basel standards pose for developing countries, see Jones and Zeitz (2017).

Are developing countries implementing Basel standards?

Many are, but selectively

In practice, Basel standards are compendia of different regulations, and regulators can choose how many of the different components to implement. The results of our research using data from the Financial Stability Institute (FSI) and in-depth case studies show that implementation in developing countries is both widespread and highly selective.

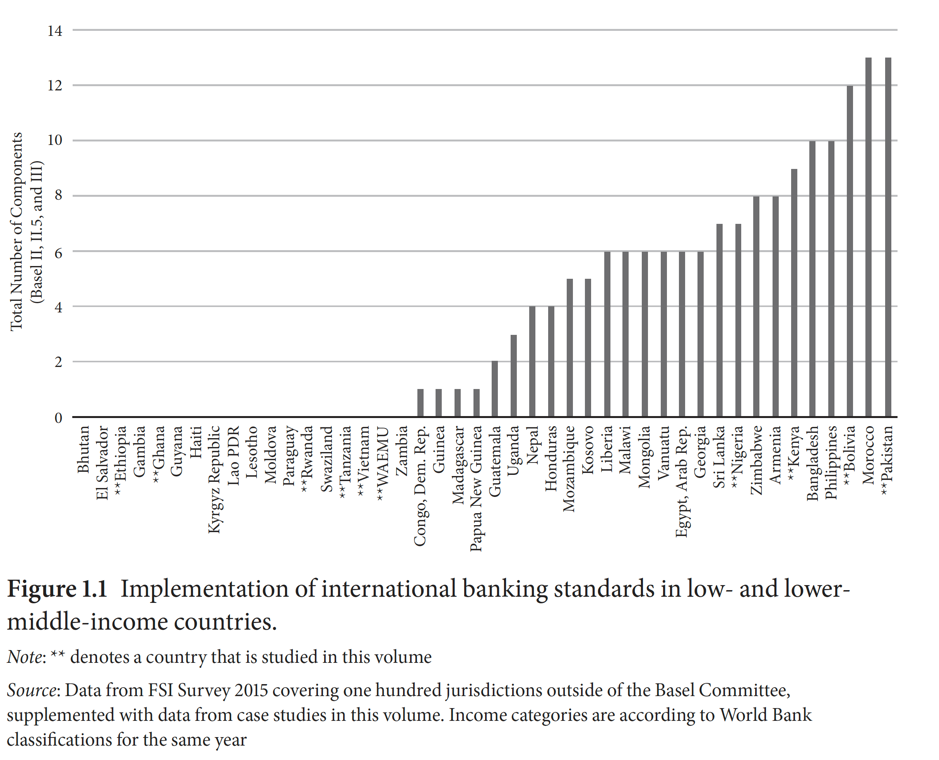

In this project we focused on implementation in low- and lower-middle-income countries (LMICs), as they are in many ways the least likely to adopt the latest and most complex international standards (Basel II and III). They have nascent and relatively small financial sectors and their regulatory institutions are particularly resource-constrained.

The latest available national survey data is from 2015 and covers 45 LMICs (Figure 1.1). It reveals that many regulators in developing LMICs are engaging with Basel standards but they are doing so in very different ways. Out of a possible total of 22 components of the latest and more complex international standards (Basel II, II.5 and III), regulators in 19 of the 45 countries were not implementing any, preferring to stay with simpler Basel I standards. Regulators in a further 21 countries had implemented between 1 and 9 components, while regulators in 5 countries had implemented between 10 and 13.

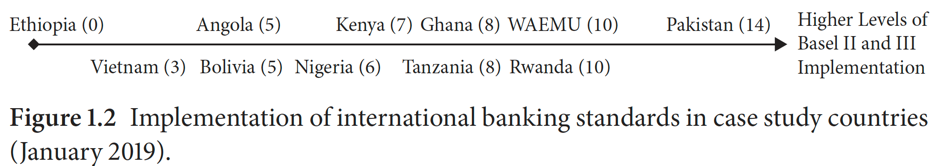

We looked in depth at Basel implementation in eleven developing countries and regions, four of which are classified as low income (Ethiopia, Rwanda, Tanzania and WAEMU) and seven as lower-middle income (Angola, Bolivia, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Pakistan and Vietnam). We found that regulators have responded in very different ways to international banking standards, with their level of engagement increasing over time. At the start of our research project in 2015, only three of the eleven jurisdictions had implemented any components of Basel II and III (Pakistan, Kenya and Nigeria). By January 2019, Ethiopia was the only country that had not implemented at least one component (Figure 1.2).

What explains these patterns of convergence and divergence? Why is it that governments in some peripheral developing countries opt to converge on international standards, while governments in other countries opt to maintain divergent standards? That is the question at the heart of this research project.

Note: Figures 1.1 and 1.2 were taken from the book The Political Economy of Bank Regulation in Developing Countries. Risk and Reputation (Oxford University Press, 2020).